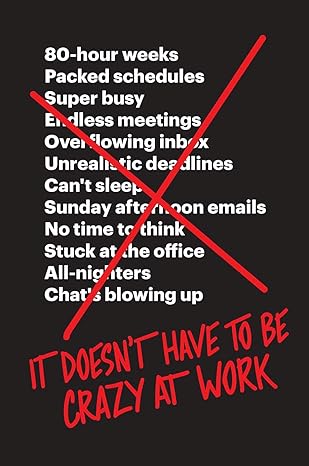

It Doesn't Have to Be Crazy at Work - by Jason Fried

Date read: 2019-02-04How strongly I recommend it: 10/10

(See my list of 150+ books, for more.)

Go to the Amazon page for details and reviews.

Fantastic book that challenges all of the old ways of working. From not having goals, to scaling back your company's growth, to level-setting salaries by roles, this is a great read for anyone having trouble maintaining high-performance at work. Not all of these ideas could or should be implemented for every company, but it does get you thinking of challenging norms and status quo of business & how companies should operate.

Contents:

- COMPANY AS A PRODUCT

- GOALS & PROJECT MANAGEMENT

- TIME MANAGEMENT

- COMPANY CULTURE

- HIRING

- BENEFITS & SALARIES

- COMMUNICATION

- DECISION-MAKING

- BEST PRACTICES

- SAYING NO

My Notes

Your company is a product.

If you want to make a product better, you have to keep tweaking, revising, and iterating. The same thing is true with a company.

But when you think of the company as a product, you ask different questions: Do people who work here know how to use the company? Is it simple? Complex? Is it obvious how it works? What's fast about it? What's slow about it? Are there bugs? What's broken that we can fix quickly and what's going to take a long time?

You're not very likely to find that key insight or breakthrough idea north of the 14th hour in the day. Creativity, progress, and impact do not yield to brute force.

Sell new customers on the new thing and let old customers keep whatever they already have. This is the way to keep the peace and maintain the calm.

Jean-Louis Gassee, who used to run Apple France, describes this situation as the choice between two tokens. When you deal with people who have trouble, you can either choose to take the token that says "It's no big deal" or the token that says "It's the end of the world." Whichever token you pick, they'll take the other.

Everyone wants to be heard and respected. It usually doesn't cost much to do, either. And it doesn't really matter all that much whether you ultimately think you're right and they're wrong. Arguing with heated feelings will just increase the burn. Keep that in mind the next time you take a token. Which one are you leaving for the customer?

Chasing goals often leads companies to compromise their morals, honesty, and integrity to reach those fake numbers. The best intentions slip when you're behind.

You can absolutely run a great business without a single goal. You don't need something fake to do something real. And if you must have a goal, how about just staying in business? Or serving your customers well? Or being a delightful place to work? Just because these goals are harder to quantify does not make them any less important.

If you stop thinking that you must change the world, you lift a tremendous burden off yourself and the people around you. There's no longer this convenient excuse for why it has to be all work all the time. The opportunity to do another good day's work will come again tomorrow, even if you go home at a reasonable time.

When you stick with planning for the short term, you get to change your mind often. And that's a huge relief! This eliminates the pressure for perfect planning and all the stress that comes with it. We simply believe that you're better off steering the ship with a thousand little inputs as you go rather than a few grand sweeping movements made way ahead of time.

Our deadlines remain fixed and fair.

The date won't move up and the date won't move back.

What's variable is the scope of the problem-the work itself. But only on the downside. You can't fix a deadline and then add more work to it. That's not fair. Our projects can only get smaller over time, not larger. As we progress, we separate the must-haves from the nice-to-haves and toss out the nonessentials.

And who makes the decision about what stays and what goes in a fixed period of time? The team that's working on it. Not the CEO, not the CTO. The team that's doing the work has control over the work. They wield the "scope hammer," as we call it.

Dependencies are tangled, intertwined teams, groups, or individuals that can't move independently of one another. Whenever someone is waiting on someone else, there's a dependency in the way.

For example, we used to try to line up release schedules for our web app and mobile apps. If we had something new on the web app, it had to wait until the iPhone and Android versions also had it before we could release everything. That slowed us down, tangled us up, and led to self-imposed frustrations. In the end, Android users didn't care whether they were using exactly the same design as iPhone users.

If you actually want to make progress, you have to narrow as you go.

After the initial dust settles, the work required to finish a project should be dwindling over time, not expanding. The deadline should be comfortably approaching, not scarily arriving.

That's why we quickly begin prototyping as soon as we can in those first two weeks. We're often looking at something real within a day or two.

But after that-after that brief period of exploration at the beginning of a project-it's time to focus in and get narrow. It's time for tunnel vision!

Week four of a six-week project should be about finishing things up and ramping things down, not coming up with big new ideas.

Always keeping the door open to radical changes only invites chaos and second-guessing. Confidently close that door. Accept that better ideas aren't necessarily better if they arrive after the train has left the station. If they're so good, they can catch the next one.

We don't throw more people at problems, we chop problems down until they can be carried across the finish line by teams of three.

Just like work expands to fill the time available, work expands to fill the team available. Small, short projects quickly become big, long projects when too many people are there to work on them.

That's why rather than jumping on every new idea right away, we make every idea wait a while. Generally a few weeks, at least. That's just enough time either to forget about it completely or to realize you can't stop thinking about it.

If you can't fit everything you want to do within 40 hours per week, you need to get better at picking what to do, not work longer hours. Most of what we think we have to do, we don't have to do at all. It's a choice, and often it's a poor one.

For example, we don't have status meetings at Basecamp. While it seems efficient to get everyone together at the same time, it isn't. It's costly, too. Eight people in a room for an hour doesn't cost one hour, it costs eight hours. Instead, we ask people to write updates daily or weekly on Basecamp for others to read when they have a free moment.

A fractured hour isn't really an hour-it's a mess of minutes. It's really hard to get anything meaningful done with such crummy input. A quality hour is 1 × 60, not 4 × 15. A quality day is at least 4 × 60, not 4 × 15 × 4.

Being productive is about occupying your time-filling your schedule to the brim and getting as much done as you can. Being effective is about finding more of your time unoccupied and open for other things besides work. Time for leisure, time for family and friends. Or time for doing absolutely nothing.

A great work ethic isn't about working whenever you're called upon. It's about doing what you say you're going to do, putting in a fair day's work, respecting the work, respecting the customer, respecting coworkers, not wasting time, not creating unnecessary work for other people, and not being a bottleneck. Work ethic is about being a fundamentally good person that others can count on and enjoy working with.

It's become fashionable to blame distractions at work on things like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube. But these things aren't the problem, any more than old-fashioned smoke breaks were the problem 30 years ago.

The major distractions at work aren't from the outside, they're from the inside. The wandering manager constantly asking people how things are going, the meeting that accomplishes little but morphs into another meeting next week, the cramped quarters into which people are crammed like sardines, the ringing phones of the sales department, or the loud lunchroom down the hall from your desk.

All subject-matter experts at Basecamp now publish office hours. But what if you have a question on Monday and someone's office hours aren't until Thursday? You wait, that's what you do. You work on something else until Thursday, or you figure it out for yourself before Thursday.

Taking someone's time should be a pain in the ass. Taking many people's time should be so cumbersome that most people won't even bother to try it unless it's REALLY IMPORTANT! Meetings should be a last resort, especially big ones.

"But how do you know if someone's working if you can't see them?" Same answer as this question: "How do you know if someone's working if you can see them?" You don't. The only way to know if work is getting done is by looking at the actual work. That's the boss's job. If they can't do that job, they should find another one.

You just can't bring your A game to every situation. Knowing when to embrace Good Enough is what gives you the opportunity to be truly excellent when you need to be.

Rather than put endless effort into every detail, we put lots of effort into separating what really matters from what sort of matters from what doesn't matter at all. The act of separation should be your highest-quality endeavor.

Doing nothing can be the hardest choice but the strongest, too.

If it's never enough, then it'll always be crazy at work.

The only way to get more done is to have less to do.

Time isn't something that can be managed. Time is time-it rolls along at the same pace regardless of how you try to wrestle with it. What you choose to spend it on is the only thing you have control over.

JOMO! The joy of missing out. It's JOMO that lets you turn off the firehose of information and chatter and interruptions to actually get the right shit done. It's JOMO that lets you catch up on what happened today as a single summary email tomorrow morning rather than with a drip-drip-drip feed throughout the day.

One way we push back against this at Basecamp is by writing monthly "Heartbeats." Summaries of the work and progress that's been done and had by a team, written by the team lead, to the entire company. All the minutiae boiled down to the essential points others would care to know. Just enough to keep someone in the loop without having to internalize dozens of details that don't matter.

Whenever executives talk about how their company is really like a big ol' family, beware. They're usually not referring to how the company is going to protect you no matter what or love you unconditionally. You know, like healthy families would. Their motive is rather more likely to be a unidirectional form of sacrifice: yours.

The best companies aren't families. They're supporters of families. Allies of families. They're there to provide healthy, fulfilling work environments so that when workers shut their laptops at a reasonable hour, they're the best husbands, wives, parents, siblings, and children they can be.

Posing real, pointed questions is the only way to convey that it's safe to provide real answers. And even then it's going to take a while. Maybe you get 20 percent of the story the first time you ask, then 50 percent after a while, and if you've really nailed it as a trustworthy boss, you may get to 80 percent. Forget about ever getting the whole story.

It takes great restraint as the leader of an organization not to keep lobbing ideas at everyone else. Every such idea is a pebble that's going to cause ripples when it hits the surface. Throw enough pebbles in the pond and the overall picture becomes as clear as mud.

The problem, as we've learned over time, is that the further away you are from the fruit, the lower it looks. Once you get up close, you see it's quite a bit higher than you thought. We assume that picking it will be easy only because we've never tried to do it before.

The people who brag about trading sleep for endless slogs and midnight marathons are usually the ones who can't point to actual accomplishments. Telling tales of endless slogs is a diversionary tactic. It's pathetic.

Remember, your brain is still active at night. It works through matters you can't address during the day. Don't you want to wake up with new solutions in your head rather than bags under your eyes?

Culture is what culture does. Culture isn't what you intend it to be. It's not what you hope or aspire for it to be. It's what you do. So do better.

Be it in hours, degrees of difficulty, or even specific benefits that emphasize seasonality, find ways to melt the monotony of work. People grow dull and stiff if they stay in the same swing for too long.

We look for candidates who are interesting and different from the people we already have.

We do better work, broader work, and more considered work when the team reflects the diversity of our customer base. "Not exactly what we already have" is a quality in itself.

For example, when we're choosing a new designer, we hire each of the finalists for a week, pay them $1,500 for that time, and ask them to do a sample project for us. Then we have something to evaluate that's current, real, and completely theirs.

In fact, junk the whole metaphor of talent wars altogether. Stop thinking of talent as something to be plundered and start thinking of it as something to be grown and nurtured, the seeds for which are readily available all over the globe for companies willing to do the work.

At the time of publication of this book, a notch over 50 percent of our employees have been here for five years or more. That's rarefied air in an industry where the average tenure at the top tech companies is less than two years.

If you don't clearly communicate to everyone else why someone was let go, the people who remain at the company will come up with their own story to explain it. Those stories will almost certainly be worse than the real reason.

We no longer negotiate salaries or raises at Basecamp. Everyone in the same role at the same level is paid the same. Equal work, equal pay.

Once every year we review market rates and issue raises automatically. Our target is to pay everyone at the company at the top 10 percent of the market regardless of their role. So whether you work in customer support or ops or programming or design, you'll be paid in the top 10 percent for that position.

Where you live has nothing to do with the quality of your work, and it's the quality of your work that we're paying you for. What difference does it make that your bed is in Boston, Barcelona, or Bangladesh?

We don't pay traditional bonuses at Basecamp, either, so our salaries are benchmarked against other companies' salaries plus bonus packages. (We used to do bonuses many years ago, but we found that they were quickly treated as expected salary, anyway. So if they ever dipped, people felt like they got a demotion.)

In our office, if someone's at their desk, we assume they're deep in thought and focused on their work. That means we don't walk up to them and interrupt them. It also means conversations should be kept to a whisper so as not to disturb anyone who could possibly hear you. Quiet runs the show.

If something is being discussed in a chat room and it's clearly too important to process one line at a time, we ask people to "write it up" instead. This goes together with the rule "If everyone needs to see it, don't chat about it." Give the discussion a dedicated, permanent home that won't scroll away in five minutes.

When we present work, it's almost always written up first. A complete idea in the form of a carefully composed multipage document. Illustrated, whenever possible. And then it's posted to Basecamp, which lets everyone involved know there's a complete idea waiting to be considered.

Take your time to gather and present your thoughts-just like the person who pitched the original idea took their time to gather and present theirs.

No one can interrupt the presenter because there's no one there to interrupt. The idea is shared whole-there's no room to stop someone, no opportunity to break someone's flow. They have the floor and it can't be taken away. And then when you're ready to present your feedback, the floor is yours.

Don't meet, write. Don't react, consider.

Someone in charge has to make the final call, even if others would prefer a different decision. Good decisions don't so much need consensus as they need commitment.

"I disagree, but let's commit" is something you'll hear at Basecamp after heated debates about specific products or strategy decisions.

What's especially important in disagree-and-commit situations is that the final decision should be explained clearly to everyone involved. It's not just decide and go, it's decide, explain, and go.

Unless you've actually done the work, you're in no position to encode it as a best practice.

All this isn't to say that best practices are of no value. They're like training wheels. When you don't know how to keep your balance or how fast to pedal, they can be helpful to get you going. But every best practice should come with a reminder to reconsider.

Rather than demand whatever it takes, we ask, What will it take? That's an invitation to a conversation. One where we can discuss strategy, make tradeoffs, make cuts, come up with a simpler approach all together, or even decide it's not worth it after all. Questions bring options, decrees burn them.

People make it because they're talented, they're lucky, they're in the right place at the right time, they know how to work with other people, they know how to sell an idea, they know what moves people, they can tell a story, they know which details matter and which don't, they can see the big and small pictures in every situation, and they know how to do something with an opportunity.

No is easier to do, yes is easier to say.

No is no to one thing. Yes is no to a thousand things.

No is a precision instrument, a surgeon's scalpel, a laser beam focused on one point. Yes is a blunt object, a club, a fisherman's net that catches everything indiscriminately.

No is specific. Yes is general.

When you say no to one thing, it's a choice that breeds choices. Tomorrow you can be as open to new opportunities as you were today.

When you say yes to one thing, you've spent that choice. The door is shut on a whole host of alternative possibilities and tomorrow is that much more limited. When you say no now, you can come back and say yes later.

If you say yes now, it's harder to say no later.

No is calm but hard. Yes is easy but a flurry.

Knowing what you'll say no to is better than knowing what you'll say yes to. Know no.

Promises pile up like debt, and they accrue interest, too. The longer you wait to fulfill them, the more they cost to pay off and the worse the regret. When it's time to do the work, you realize just how expensive that yes really was.