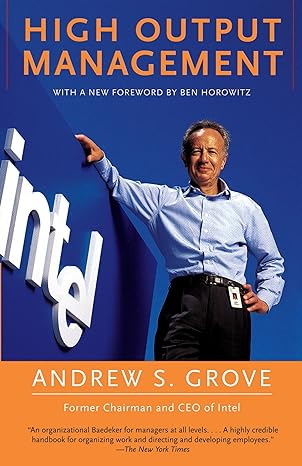

High Output Management - by Andrew S. Grove

Date read: 2018-09-27How strongly I recommend it: 10/10

(See my list of 150+ books, for more.)

Go to the Amazon page for details and reviews.

A must read for any existing or new manager. Andrew Grove walks through the key deliverables and expectations of managers in a step-by-step process. From managing production, making decisions, assessing talent, even how to run meetings. With the focus all around how to yield the greatest output.

Contents:

- PRODUCTION MANAGEMENT

- GENERAL MANAGEMENT

- TIME MANAGEMENT

- MEETINGS

- ONE-ON-ONES

- STAFF MEETINGS

- OPERATION REVIEWS

- MISSION-ORIENTED MEETINGS

- DECISION-MAKING

- PLANNING STEP 1 — ENVIRONMENTAL DEMAND

- PLANNING STEP 2 — PRESENT STATUS

- PLANNING STEP 3 — WHAT TO DO TO CLOSE THE GAP

- MBO (MANAGING BY OBJECTIVE)

- MATRIX ORGANIZATIONS

- MANAGING THE TEAM

- TASK RELEVANT MATURITY

- PERFORMANCE REVIEW

- INTERVIEWING

- SAVING A VALUED EMPLOYEE

- TRAINING

My Notes

What are the rules of the new environment? First, everything happens faster. Second, anything that can be done will be done, if not by you, then by someone else. Let there be no misunderstanding : These changes lead to a less kind, less gentle, and less predictable workplace.

You need to develop a higher tolerance for disorder. Now, you should still not accept disorder. In fact, you should do your best to drive what’s around you to order.

“Let chaos reign, then rein in chaos.”

As a micro CEO, you can improve your own and your group’s performance and productivity, whether or not the rest of the company follows suit.

The output of a manager is the output of the organizational units under his or her supervision or influence.

High managerial productivity, I argue, depends largely on choosing to perform tasks that possess high leverage.

A team will perform well only if peak performance is elicited from the individuals in it.

A manager’s output = the output of his organization + the output of the neighboring organizations under his influence.

When a person is not doing his job, there can only be two reasons for it. The person either can’t do it or won’t do it; he is either not capable or not motivated. ”This insight enables a manager to dramatically focus her efforts. All you can do to improve the output of an employee is motivate and train. There is nothing else.

We construct our production flow by starting with the longest (or most difficult, or most sensitive, or most expensive) step and work our way back.

The three fundamental types of production operations:

Raw material inventory. But how large should it be? The principle to be applied here is that you should have enough to cover your consumption rate for the length of time it takes to replace your raw material. That means if your egg man comes by and delivers once a day, you want to keep a day’s worth of inventory on hand to protect yourself.

A common rule we should always try to heed is to detect and fix any problem in a production process at the

lowest-value stage possible.

To run your operation well, you will need a set of good indicators, or measurements.

Which five pieces of information would you want to look at each day, immediately upon arriving at your office?

You want to have some kind of quality indicator.

Indicators tend to direct your attention toward what they are monitoring. It is like riding a bicycle: you will probably steer it where you are looking. If, for example, you start measuring your inventory levels carefully, you are likely to take action to drive your inventory levels down, which is good up to a point. But your inventories could become so lean that you can’t react to changes in demand without creating shortages. So because indicators direct one’s activities, you should guard against overreacting. This you can do by pairing indicators , so that together both effect and counter-effect are measured. Thus, in the inventory example, you need to monitor both inventory levels and the incidence of shortages. A rise in the latter will obviously lead you to do things to keep inventories from becoming too low.

The first rule is that a measurement — any measurement — is better than none. But a genuinely effective indicator will cover the output of the work unit and not simply the activity involved. Obviously, you measure a salesman by the orders he gets (output), not by the calls he makes (activity).

What you measure should be a physical, countable thing.

Leading indicators give you one way to look inside the black box by showing you in advance what the future might look like.

Of course, for leading indicators to do you any good, you must believe in their validity.

Leading indicators might include the daily monitors we use to run our breakfast factory, from machine downtime records to an index of customer satisfaction — both of which can tell us if problems lie down the road.

Also valuable are trend indicators. These show output (breakfasts delivered, software modules completed, vouchers processed) measured against time (performance this month versus performance over a series of previous months), and also against some standard or expected level.

Another sound way to anticipate the future is through the use of the stagger chart, which forecasts an output over the next several months. The chart is updated monthly, so that each month you will have an updated version of the then - current forecast information as compared to several prior forecasts. You can readily see the variation of one forecast from the next, which can help you anticipate future trends better than if you used a simple trend chart.

What works better is to ask both the manufacturing and the sales departments to prepare a forecast, so that people are responsible for performing against their own predictions.

It is a good idea to use stagger charts in both the manufacturing and sales forecasts. As noted, they will show the trend of change from one forecast to another, as well as the actual results. By repeatedly observing the variance of one forecast from another, you will continually pin down the causes of inaccuracy and improve your ability to forecast both orders and the availability of product.

To get acceptable quality at the lowest cost, it is vitally important to reject defective material at a stage where its accumulated value is at the lowest possible level.

A manager’s output = The output of his organization + The output of the neighboring organizations under his influence.

Individual contributors who gather and disseminate know-how and information should also be seen as middle managers, because they exert great power within the organization.

A manager must keep many balls in the air at the same time and shift his energy and attention to activities that will most increase the output of his organization. In other words, he should move to the point where his leverage will be the greatest.

Reports are more a medium of self-discipline than a way to communicate information. Writing the report is important; reading it often is not.

There is an especially efficient way to get information, much neglected by most managers. That is to visit a particular place in the company and observe what’s going on there.

A manager not only gathers information but is also a source of it. He must convey his knowledge to members of his own organization and to other groups he influences. Beyond relaying facts, a manager must also communicate his objectives, priorities, and preferences as they bear on the way certain tasks are approached. This is extremely important, because only if the manager imparts these will his subordinates know how to make decisions themselves that will be acceptable to the manager, their supervisor. Thus, transmitting objectives and preferred approaches constitutes a key to successful delegation.

Nudging - to nudge an individual or a meeting in the direction you would like. This is an immensely important managerial activity in which we engage all the time, and it should be carefully distinguished from decision-making that results in firm, clear directives. In reality, for every unambiguous decision we make, we probably nudge things a dozen times.

How you handle your own time is, in my view, the single most important aspect of being a role model and leader.

You can never wash your hands of a task. Even after you delegate it, you are still responsible for its accomplishment, and monitoring the delegated task is the only practical way for you to ensure a result. Monitoring is not meddling, but means checking to make sure an activity is proceeding in line with expectations. Because it is easier to monitor something with which you are familiar, if you have a choice you should delegate those activities you know best.

A variable approach should be employed, using different sampling schemes with various subordinates; you should increase or decrease your frequency depending on whether your subordinate is performing a newly delegated task or one that he has experience handling. How often you monitor should not be based on what you believe your subordinate can do in general, but on his experience with a specific task and his prior performance with it — his task - relevant maturity,

The manager should only go into details randomly, just enough to try to ensure that the subordinate is moving ahead satisfactorily. To check into all the details of a delegated task would be like quality assurance testing 100 percent of what manufacturing turned out.

As a rule of thumb, a manager whose work is largely supervisory should have six to eight subordinates; three or four are too few and ten are too many. This range comes from a guideline that a manager should allocate about a half day per week to each of his subordinates.

We should do everything we can to prevent little stops and starts in our day as well as interruptions brought on by big emergencies. Even though some of the latter are unavoidable, we should always be looking for sources of future high-priority trouble by cutting windows into the black box of our organization. Recognizing you’ve got a time bomb on your hands means you can address a problem when you want to, not after the bomb has gone off.

The most common problem cited for managers was uncontrolled interruptions.

If you can pin down what kind of interruptions you’re getting, you can prepare standard responses for those that pop up most often. Customers don’t come up with totally new questions and problems day in and day out, and because the same ones tend to surface repeatedly, a manager can reduce time spent handling interruptions using standard responses. Having them available also means that a manager can delegate much of the job to less experienced personnel.

Many interruptions that come from your subordinates can be accumulated and handled not randomly, but at staff and at one-on-one meetings. If such meetings are held regularly, people can’t protest too much if they’re asked to batch questions and problems for scheduled times, instead of interrupting you whenever they want.

So, instead of going into hiding, a manager can hang a sign on his door that says, “I am doing individual work. Please don’t interrupt me unless it really can’t wait until 2:00.” Then hold an open office hour, and be completely receptive to anybody who wants to see you. The key is this: understand that interrupters have legitimate problems that need to be handled. That’s why they’re bringing them to you. But you can channel the time needed to deal with them into organized, scheduled form by providing an alternative to interruption — a scheduled meeting or an office hour.

The point is to impose a pattern on the way a manager copes with problems. To make something regular that was once irregular is a fundamental production principle, and that’s how you should try to handle the interruptions that plague you.

A meeting is nothing less than the medium through which managerial work is performed. That means we should not be fighting their very existence, but rather using the time spent in them as efficiently as possible.

In the first kind of meeting, called a process - oriented meeting, knowledge is shared and information is exchanged. Such meetings take place on a regularly scheduled basis.

Meetings of this sort, called mission-oriented, frequently produce a decision. They are ad hoc affairs, not scheduled long in advance, because they usually can’t be.

Process-Oriented Meetings - the people attending should know how the meeting is run, what kinds of substantive matters are discussed, and what is to be accomplished.

Given the regularity, you and the others attending can begin to forecast the time required for the kinds of work to be done. Hence, a “production control” system, as recorded on various calendars, can take shape, which means that a scheduled meeting will have minimum impact on other things people are doing.

Its main purpose is mutual teaching and exchange of information. By talking about specific problems and situations, the supervisor teaches the subordinate his skills and know-how, and suggests ways to approach things. At the same time, the subordinate provides the supervisor with detailed information about what he is doing and what he is concerned about.

You should have one-on-ones frequently (for example, once a week) with a subordinate who is inexperienced in a specific situation and less frequently (perhaps once every few weeks) with an experienced veteran.

Another consideration here is how quickly things change in a job area. In marketing, for example, the pace may be so rapid that a supervisor needs to have frequent one-on-ones to keep current on what’s happening.

I feel that a one-on-one should last an hour at a minimum. Anything less, in my experience, tends to make the subordinate confine himself to simple things that can be handled quickly.

I think you should have the meeting in or near the subordinate’s work area if possible. A supervisor can learn a lot simply by going to his subordinate’s office. Is he organized or not? Does he repeatedly have to spend time looking for a document he wants? Does he get interrupted all the time? Never? And in general, how does the subordinate approach his work?

It should be regarded as the subordinate’s meeting, with its agenda and tone set by him.

Prepare an outline, which is very important because it forces him to think through in advance all of the issues and points he plans to raise.

The subordinate should then walk the supervisor through all the material.

What should be covered in a one-on-one? We can start with performance figures, indicators used by the subordinate, such as incoming order rates, production output, or project status. Emphasis should be on indicators that signal trouble. The meeting should also cover anything important that has happened since the last meeting: current hiring problems, people problems in general, organizational problems and future plans, and — very, very important — potential problems.

“The good time users among managers do not talk to their subordinates about their problems but they know how to make the subordinates talk about theirs.”

How is this done? By applying Grove’s Principle of Didactic Management, “Ask one more question!” When the supervisor thinks the subordinate has said all he wants to about a subject, he should ask another question. He should try to keep the flow of thoughts coming by prompting the subordinate with queries until both feel satisfied that they have gotten to the bottom of a problem.

Both the supervisor and subordinate should have a copy of the outline and both should take notes on it.

A real time - saver is using a “hold” file where both the supervisor and subordinate accumulate important but not altogether urgent issues for discussion at the next meeting.

The supervisor should also encourage the discussion of heart-to-heart issues during one-on-ones, because this is the perfect forum for getting at subtle and deep work-related problems affecting his subordinate. Is he satisfied with his own performance? Does some frustration or obstacle gnaw at him? Does he have doubts about where he is going?

What should be discussed at a staff meeting? Anything that affects more than two of the people present.

If the meeting degenerates into a conversation between two people working on a problem affecting only them, the supervisor should break it off and move on to something else that will include more of the staff, while suggesting that the two continue their exchange later.

It should be mostly controlled, with an agenda issued far enough in advance that the subordinates will have had the chance to prepare their thoughts for the meeting. But it should also include an “open session” — a designated period of time for the staff to bring up anything they want.

A supervisor should never use staff meetings to pontificate, which is the surest way to undermine free discussion and hence the meeting’s basic purpose.

The format here should include formal presentations in which managers describe their work to other managers who are not their immediate supervisors, and to peers in other parts of the company.

I would recommend four minutes of presentation and discussion time per visual aid, which can include tables, numbers, or graphics.

Pay attention and jot down things you’ve heard that you might try. Ask questions if something is not clear to you and speak up if you can’t go along with an approach being recommended. And if a presenter makes a factual error, it is your responsibility to go on record.

So before calling a meeting, ask yourself: What am I trying to accomplish? Then ask, is a meeting necessary? Or desirable? Or justifiable? Don’t call a meeting if all the answers aren’t yes.

An estimate of the dollar cost of a manager’s time, including overhead, is about $100 per hour. So a meeting involving ten managers for two hours costs the company $2,000. Most expenditures of $2,000 have to be approved in advance by senior people — like buying a copying machine or making a transatlantic trip — yet a manager can call a meeting and commit $2,000 worth of managerial resources at a whim.

Keep in mind that a meeting called to make a specific decision is hard to keep moving if more than six or seven people attend. Eight people should be the absolute cutoff. Decision-making is not a spectator sport, because onlookers get in the way of what needs to be done.

The faster the change in the know-how on which the business depends or the faster the change in customer preferences, the greater the divergence between knowledge and position power is likely to be.

The first stage should be free discussion, in which all points of view and all aspects of an issue are openly welcomed and debated. The greater the disagreement and controversy, the more important becomes the word free.

The next stage is reaching a clear decision. Again, the greater the disagreement about the issue, the more important becomes the word clear. In fact, particular pains should be taken to frame the terms of the decision with utter clarity.

Finally, everyone involved must give the decision reached by the group full support. This does not necessarily mean agreement: so long as the participants commit to back the decision, that is a satisfactory outcome.

An organization does not live by its members agreeing with one another at all times about everything. It lives instead by people committing to support the decisions and the moves of the business.

Another desirable and important feature of the model is that any decision be worked out and reached at the lowest competent level. The reason is that this is where it will be made by people who are closest to the situation and know the most about it.

Decision-making should occur in the middle ground, between reliance on technical knowledge on the one hand, and on the bruises one has received from having tried to implement and apply such knowledge on the other.

The Peer-Group Syndrome - Peers tend to look for a more senior manager, even if he is not the most competent or knowledgeable person involved, to take over and shape a meeting. Why? Because most people are afraid to stick their necks out.

If the peer-group syndrome manifests itself, and the meeting has no formal chairman, the person who has the most at stake should take charge. If that doesn’t work, one can always ask the senior person present to assume control.

As a manager, you should remind yourself that each time an insight or fact is withheld and an appropriate question is suppressed, the decision-making process is less good than it might have been.

If the rest of the group or a senior - level manager vetoed a junior person or opposed a position he was advocating, the junior manager might lose face in front of his peers. This, even more than fear of sanctions or even of the loss of job, makes junior people hang back and let the more senior people set the likely direction of decision-making.

Don’t push for a decision prematurely. Make sure you have heard and considered the real issues rather than the superficial comments that often dominate the early part of a meeting. But if you feel that you have already heard everything, that all sides of the issue have been raised, it is time to push for a consensus — and failing that, to step in and make a decision.

One of the manager’s key tasks is to settle six important questions in advance:

If the final word has to be dramatically different from the expectations of the people who participated in the decision-making process, make your announcement but don’t just walk away from the issue. People need time to adjust, rationalize, and in general put their heads back together. Adjourn, reconvene the meeting after people have had a chance to recover, and solicit their views of the decision at that time. This will help everybody accept and learn to live with the unexpected.

A middle manager I once knew came straight from one of the better business schools and possessed what we might call a “John Wayne” mentality. Having become frustrated with the way Intel made decisions, he quit. He joined a company where his employers assured him during the interview that people were encouraged to make individual decisions which they were then free to implement. Four months later, he came back to Intel. He explained that if he could make decisions without consulting anybody, so could everybody else.

Your environment is made up of other such groups that directly influence what you do.

You should attempt to determine your customers’ expectations and their perception of your performance.

Once you have established what constitutes your environment, you need to examine it in two time frames — now, and sometime in the future, let’s say in a year. The questions then become: What do my customers want from me now? Am I satisfying them? What will they expect from me one year from now?

You do this by listing your present capabilities and the projects you have in the works.

Undertaking new tasks or modifying old ones to close the gap between your environmental demand and what your present activities will yield. The first question is, What do you need to do to close the gap? The second is, What can you do to close the gap?

The set of actions you decide upon is your strategy.

As you formulate in words what you plan to do, the most abstract and general summary of those actions meaningful to you is your strategy. What you’ll do to implement the strategy is your tactics.

As you plan you must answer the question: What do I have to do today to solve — or better, avoid — tomorrow’s problem?

You implement only that portion of a plan that lies within the time window between now and the next time you go through the exercise.

Be careful not to plan too frequently, allowing ourselves time to judge the impact of the decisions we made and to determine whether our decisions were on the right track or not.

A successful MBO system needs only to answer two questions:

An MBO system should set objectives for a relatively short period. For example, if we plan on a yearly basis, the corresponding MBO system’s time frame should be at least as often as quarterly or perhaps even monthly.

An MBO system should provide par excellence is focus. This can only happen if we keep the number of objectives small.

All large organizations with a common business purpose end up in a hybrid organizational form.

In matrix management, to make such a body work requires the voluntary surrender of individual decision-making to the group.

To be sure, neither that form nor the need for dual reporting is an excuse for needless busywork, and we should mercilessly slash away unnecessary bureaucratic hindrance, apply work simplification to all we do, and continually subject all established requirements for coordination and consultation to the test of common sense.

The single most important task of a manager is to elicit peak performance from his subordinates.

A manager has two ways to tackle the issue: through training and motivation.

Two inner forces can drive a person to use all of his capabilities. He can be competence - driven or achievement - driven.

The former concerns itself with job or task mastery. A virtuoso violinist who continues to practice day after day is obviously moved by something other than a need for esteem and recognition.

The achievement - driven path to self - actualization is not quite like this. Some people — not the majority — are moved by an abstract need to achieve in all that they do.

Both competence - and achievement - oriented people spontaneously try to test the outer limits of their abilities.

In an MBO system, for example, objectives should be set at a point high enough so that even if the individual (or organization) pushes himself hard, he will still only have a fifty-fifty chance of making them.

We want to cultivate achievement - driven motivation, we need to create an environment that values and emphasizes output.

A simple test can be used to determine where someone is in the motivational hierarchy. If the absolute sum of a raise in salary an individual receives is important to him, he is working mostly within the physiological or safety modes. If, however, what matters to him is how his raise stacks up against what other people got, he is motivated by esteem / recognition or self - actualization, because in this case money is clearly a measure.

Given a specific task, fear of failure can spur a person on, but if it becomes a preoccupation, a person driven by a need to achieve will simply become conservative.

The role of the manager here is also clear: it is that of the coach. First, an ideal coach takes no personal credit for the success of his team, and because of that his players trust him. Second, he is tough on his team. By being critical, he tries to get the best performance his team members can provide. Third, a good coach was likely a good player himself at one time. And having played the game well, he also understands it well.

The conclusion is that varying management styles are needed as task-relevant maturity (TRM) varies.

When the TRM is low, the most effective approach is one that offers very precise and detailed instructions, wherein the supervisor tells the subordinate what needs to be done, when, and how:

As the TRM of the subordinate grows, the most effective style moves from the structured to one more given to communication, emotional support, and encouragement, in which the manager pays more attention to the subordinate as an individual than to the task at hand.

As the TRM becomes even greater, the effective management style changes again. Here the manager’s involvement should be kept to a minimum, and should primarily consist of making sure that the objectives toward which the subordinate is working are mutually agreed upon.

But regardless of what the TRM may be, the manager should always monitor a subordinate’s work closely enough to avoid surprises.

Not make a value judgment and consider a structured management style less worthy than a communication-oriented one. What is “nice” or “not nice” should have no place in how you think or what you do. Remember, we are after what is most effective.

The responsibility for teaching the subordinate must be assumed by his supervisor, and not paid for by the customers of his organization, internal or external.

Everyone must decide for himself what is professional and appropriate here. A test might be to imagine yourself delivering a tough performance review to your friend. Do you cringe at the thought? If so, don’t make friends at work. If your stomach remains unaffected, you are likely to be someone whose personal relationships will strengthen work relationships.

If performance matters in your operation, performance reviews are absolutely necessary.

To make an assessment less difficult, a supervisor should clarify in his own mind in advance what it is that he expects from a subordinate and then attempt to judge whether he performed to expectations.

The biggest problem with most reviews is that we don’t usually define what it is we want from our subordinates, and, as noted earlier, if we don’t know what we want, we are surely not going to get it.

Ultimately what you are after is the performance of the group, but the manager is there to add value in some way.

You must ask: Is he doing anything with his group? Is he hiring new people? Is he training the people he has, and doing other things that are likely to improve the output of the team in the future?

The performance rating of a manager cannot be higher than the one we would accord to his organization!

There are three L’s to keep in mind when delivering a review:

On the One Hand… On the Other Hand...Most reviews probably fall into this category, containing both positive and negative assessments. Common problems here include superficiality, clichés, and laundry lists of unrelated observations.

If his responses — verbal and nonverbal — do not completely assure you that what you’ve said has gotten through, it is your responsibility to keep at it until you are satisfied that you have been heard and understood.

Listen with all your might to make sure your subordinate is receiving your message, and don’t stop delivering it until you are satisfied that he is.

The fact is that a person can only absorb so many messages at one time, especially when they deal with his own performance. The purpose of the review is not to cleanse your system of all the truths you may have observed about your subordinate, but to improve his performance. So here less may very well be more.

First, consider as many aspects of your subordinate’s performance as possible.

Then sit down with a blank piece of paper. As you consider your subordinate’s performance, write everything down on the paper. Do not edit in your head. Get everything down, knowing that doing so doesn’t commit you to do anything.

Now, from your worksheet, look for relationships between the various items listed. You will probably begin to notice that certain items are different manifestations of the same phenomenon, and that there may be some indications why a certain strength or weakness exists. When you find such relationships, you can start calling them “messages” for the subordinate.

Once your list of messages has been compiled, ask yourself if your subordinate will be able to remember all of the messages you have chosen to deliver. If not, you must delete the less important ones. Remember, what you couldn’t include in this review, you can probably take up in the next one.

Preferably, a review should not contain any surprises, but if you uncover one, swallow hard and bring it up.

He has to take the biggest step: namely assuming responsibility. He has to say not only that there is a problem but that it is his problem. This is fateful, because it means work: “If it is my problem, I have to do something about it. If I have to do something, it is likely to be unpleasant and will definitely mean a lot of work on my part.”

It is the reviewer’s job to get the subordinate to move through all of the stages to that of assuming responsibility, though finding the solution should be a shared task.

If the supervisor wants to go on to find the solution when the subordinate is still denying or blaming others, nothing can happen. Knowing where you are will help you both move through the stages together.

It seems that for an achiever the supervisor’s effort goes into determining and justifying the judgment of the superior performance, while giving little attention to how he could do even better.

Shouldn’t we spend more time trying to improve the performance of our stars? Concentrating on the stars is a high - leverage activity : if they get better, the impact on group output is very great indeed.

In my experience, the best thing to do is to give your subordinate the written review sometime before the face-to-face discussion.

You might have a scheme in which a manager’s performance bonus is based on three factors. The first would include his individual performance only, as judged by his supervisor. The second would account for his immediate team’s objective performance, his department perhaps. The third factor would be linked to the overall financial performance of the corporation.

The purpose of the interview is to:

The applicant should do 80 percent of the talking during the interview, and what he talks about should be your main concern.

When things go off the track, get them back on quickly. Apologize if you like, and say, “I would like to change the subject to X, Y, or Z.” The interview is yours to control, and if you don’t, you have only yourself to blame.

An interview produces the most insight if you steer the discussion toward subjects familiar to both you and the candidate. The person should talk about himself, his experience, what he has done and why, what he would have done differently if he had it to do over, and so forth, but this should be done in terms familiar to you, so that you can evaluate its significance. In short, make sure the words used mean the same thing to both of you.

Don’t worry about being blunt; direct questions tend to bring direct answers, and when they don’t, they produce other forms of insight into the candidate.

Asking a candidate to handle a hypothetical situation can also enlighten you.

The candidate can tell you a great deal about his capabilities, skills, and values by asking you questions. Ask the candidate what he would like to know about you, the company, or the job. The questions he asks will tell you what he already knows about the company, what he would like to know more about, and how well prepared he is for the interview.

In the end careful interviewing doesn’t guarantee you anything, it merely increases your odds of getting lucky.

Drop what you are doing. Sit him down and ask him why he is quitting. Let him talk — don’t argue about anything with him.

You have to convey to him by what you do that he is important to you, and you have to find out what is really troubling him. Don’t try to change his mind at this point, but buy time. After he’s said all he has to say, ask for whatever time you feel is necessary to prepare yourself for the next round. But know that you must follow through on whatever you’ve committed yourself to do.

“You did not blackmail us into doing anything we shouldn’t have done anyway. When you almost quit, you shook us up and made us aware of the error of our ways. We are just doing what we should have done without any of this happening.”

Then your subordinate may say he’s accepted a job somewhere else and can’t back out. You have to make him quit again. You say he’s really made two commitments: first to a potential employer he only vaguely knows, and second to you, his present employer. And commitments he has made to the people he has been working with daily are far stronger than one made to a casual new acquaintance.

Most managers seem to feel that training employees is a job that should be left to others, perhaps to training specialists. I, on the other hand, strongly believe that the manager should do it himself.

For training to be effective, it has to be closely tied to how things are actually done in your organization.

For training to be effective, it also has to maintain a reliable, consistent presence. Employees should be able to count on something systematic and scheduled, not a rescue effort summoned to solve the problem of the moment. In other words, training should be a process, not an event.

At Intel we distinguish between two different training tasks. The first task is teaching new members of our organization the skills needed to perform their jobs. The second task is teaching new ideas, principles, or skills to the present members of our organization.

Ask the people working for you what they feel they need. They are likely to surprise you by telling you of needs you never knew existed.

Take an inventory of the manager - teachers and instructional materials available to help deliver training on items on your list. Then assign priorities among these items.