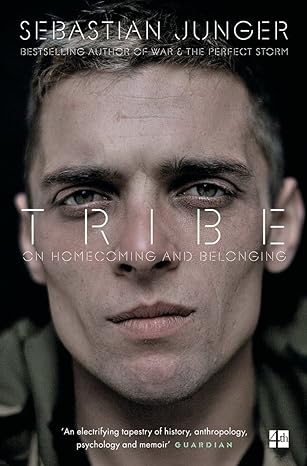

Tribe: On Homecoming and Belonging - by Sebastian Junger

Date read: 2017-02-25How strongly I recommend it: 6/10

(See my list of 150+ books, for more.)

Go to the Amazon page for details and reviews.

So much of what makes our lives so great also makes us so alone. Good read on the importance of community and how it can foster and grow in times of disaster or war.

Contents:

My Notes

Robert Frost famously wrote that home is the place where, when you have to go there, they have to take you in. The word "tribe" is far harder to define, but a start might be the people you feel compelled to share the last of your food with.

Early humans would most likely have lived in nomadic bands of around fifty people and they would have almost never been alone.

As affluence and urbanization rise in a society, rates of depression and suicide tend to go up rather than down.

Human beings need three basic things in order to be content: 1) they need to feel competent at what they do 2) they need to feel authentic in their lives and 3) they need to feel connected to others.

Infants in hunter-gatherer societies are carried by their mothers as much as 90 percent of the time, but in America during the 1970s, mothers maintained skin-to-skin contact with babies as little as 16 percent of the time, which is a level that traditional societies would probably consider a form of child abuse.

The point of making children sleep alone is to make them "self-soothing," but that clearly runs contrary to our evolution. Humans are primates - we share 98 percent of our DNA with chimpanzees - and primates almost never leave infants unattended, because they would be extremely vulnerable to predators.

The fact that a group of people can cost American society several trillion dollars in losses - roughly one-quarter of that year's gross domestic product - and not be tried for high crimes shows how completely de-tribalized the country has become.

Communities that have been devastated by natural or man-made disasters almost never lapse into chaos and disorder; if anything, they become more just, more egalitarian, and more deliberately fair to individuals. (Despite erroneous news reports, New Orleans experienced a drop in crime rates after Hurricane Katrina, and much of the "looting" turned out to be people looking for food.)

Social bonds were reinforced during disasters, and that people overwhelmingly devoted their energies toward the good of the community rather than just themselves.

Intensive training and danger create what is known as unit cohesion - strong emotional bonds within the company or the platoon - and high unit cohesion is correlated with lower rates of psychiatric breakdown.

Studies from around the world show that recovery from war or any trauma is heavily influenced by the society one belongs to, and there are societies that make that process relatively easy. Modern society does not seem to be one of them.

Our tribalism is to an extremely narrow group of people: our children, our spouse, maybe our parents. Our society is alienating, technical, cold, and mystifying. Our fundamental desire, as human beings, is to be close to others, and our society does not allow for that.

The closer the public is to the actual combat, the better the war will be understood and the less difficulty soldiers will have when they come home.

Because modern society has almost completely eliminated trauma and violence from everyday life, anyone who does suffer those things is deemed to be extraordinarily unfortunate. This gives people access to sympathy and resources but also creates an identity of victimhood that can delay recovery.

Three factors that seem to crucially affect a combatant's transition back into civilian life:

Two of the behaviors that set early humans apart were the systematic sharing of food and altruistic group defense. Soldiers experience this tribal way of thinking at war, but when they come home they realize that the tribe they were actually fighting for wasn't their country, it was their unit.

The last time the United States experienced that kind of unity was after the terrorist attacks of September 11. There were no rampage shootings for the next two years. The effect was particularly pronounced in New York City, where rates of violent crime, suicide, and psychiatric disturbances dropped immediately. New York's suicide rate dropped by around 20 percent in the six months following the attacks and the murder rate dropped by 40 percent.

veterans who were being treated for PTSD at the VA experienced a significant drop in their symptoms in the months after the September 11 attacks.